Reversing Migration: How effective is a Return Migration Strategy?

Analysis

Introduction

Since the uprisings in several North African and Middle Eastern countries (2010-2017) mass migration operates as an epidemic of hysteria, in which large groups of different nationalities, display similar agitation and state of mind, vulnerable to rumours, blind to dangers and risks, and dreaming of an eldorado, which, in most cases, turns to be a mere illusion. Therefore, in many regards, mass migration to Europe and mass hysteria share several common characteristics, so much so that it could be said that mass migration is a form of mass hysteria, which ends in a mass delusion. A lot has been said about the frenzy and the fury of mass migration.

That being the case, little has been said about the measures able to deconstruct the narrative that generates mass migration. Restrictive and protective policies such as border enforcement are obviously effective as technical solutions. In particular, the Hungarian fence has largely contributed to stop mass migration through the Balkans, putting into place a hard factor to ignore in any trip to Europe, immensely more difficult and costly now, and less subject to excess and disorder as was the situation prior to installing the fence. However, such measures do not work on the source of the problem, and cannot control the situation in the long run, as usually the smugglers, the NGOs and the migrants look for other ways to enter “the promised land”. An effective strategy can only work if it addresses the problem in the downstream. It is suggested that preventing migration, and especially through return migration could render strategic results as return migration works on the roots of mass migration, that is invalidating “false rumours about paradisiacal lands”.

This paper seeks to identify some recent data which shows the current trends of return migration and the possible ways to maximise the effect return migration could have on preventing migration. This paper assesses the effectiveness of this strategy and argues that despite the potential return migration could exercise on addressing the convulsion and the outbreak of movements of mass migration in the Western European context, it is still indecisive in bringing a solution to mass migration.

1. Recent cases of return migration

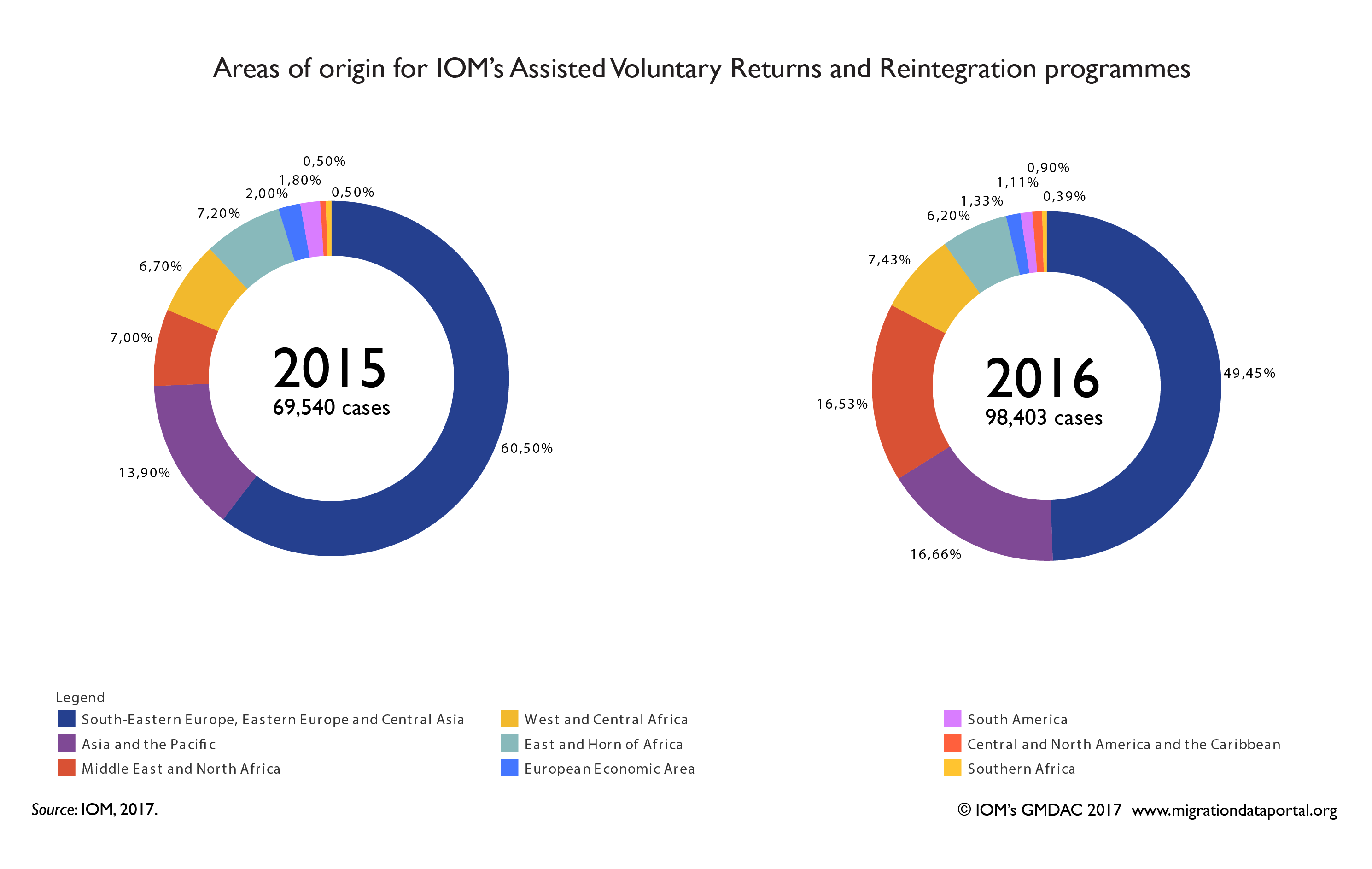

Although the current public debate in Europe on migration seems to provide limited space to return migration, global actors of migration are aware of the potential return migration could represent for addressing mass migration at its roots, and even promote its effective side. The International Organisation for Migration, the United Migration Agency, defines assisted voluntary return as “Administrative, logistical, financial and reintegration support to rejected asylum seekers, victims of trafficking in human beings, stranded migrants, qualified nationals and other migrants unable or unwilling to remain in the host country who volunteer to return to their countries of origin”[1]. The International Organisation for Migration, praises its recent work on return migration in 2016, as the following snapshot shows:

Source: iom.int

In his speech on the State of the Union, on 13 September 2017, Jean-Claude Junker, the president of the European Commission called, with regard to migration, to ”put an emphasis on returns, solidarity with Africa and opening legal pathways…(stating that) when it comes to returns, I would like to repeat that people who have no right to stay in Europe must be returned to their countries of origin. When only 36% of irregular migrants are returned, it is clear we need to significantly step up our work. This is the only way Europe will be able to show solidarity with refugees in real need of protection”.[2] In this connection, Le Monde reported that a plan by the European Commission, supported by the French President Emmanuel Macron intends “to release an additional 500 million euros to help the countries carrying out relocations and accelerating the return of 1.5 million migrants present on its territory and who can not claim asylum, knowing that the return procedures are cumbersome and disparate, and that the Commission hopes to strengthen the ‘return’ department of the Border and Coast Guard Agency”.[3]

In December 2016, France made the headlines in Europe as it offered 2,500 euros to migrants to return to their home country. Some accepted the offer, like the seventy Afghans who flew by plane to their homeland in November 2016.[4] The French government during François Hollande’s presidency (2012-2017) made return one of the main policies of migration management. According to Le Monde, in 2016, the authorities “have convinced 3,051 people to return home, 16% more than in 2015. The Afghans have been the most numerous to accept the return procedure, and some 400 have already left in 2016, against only nineteen on the whole of 2015. The Chinese (379 departures), the Russians (244), the Algerians (243), the Ukrainians (167) and the Afghans are the five nationalities to have most accepted the return plan. In addition, there are 75 Iraqis and a Syrian family who chose to return. The French government offers a reintegration assistance of 3,500 euros per person to start a business. Under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy (2007- 2012), 9 million euros were spent on 8 278 returns”.[5]

The effectiveness of a return migration policy depends on the place it occupies in the migration strategy. If the latter is centred on relocation, a return plan would only attract a minor number of migrants, probably those who had still another option of social promotion in their countries of origin. As thousands go back, millions arrive, and if hundred thousands stay, it is still an ineffective strategy. A significant number of returned could lead to lesser candidates for migration as return would spoil the hysterical urge of mass migration. A mass return migration, even if done occasionally but highly mediatised, could still aerate the space, and alleviate the burden.

In Germany, Merkel’s government issued a new online portal which aims to make returning “the better option”[6]. Different reasons push the migrants to return home from Germany: “to care for an ill relative, missing family members who were left behind, the barrier of language, inability to adapt, rejection of the asylum request etc”.[7] According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), “54,096 asylum-seekers voluntarily left Germany in 2016. By the end of April 2017, around 11,000 had left. Currently, 30,000 rejected asylum-seekers are required to leave Germany. In 2016, Germany sent back 25,375 failed asylum-seekers, an increase of 21.5 percent compared to 2015. Between January and March 2017, 8,468 refugees left the country of their own will compared 13,848 returnees over the same time period in 2016. This represents a decrease of 40%”. [8] The latter decrease could be explained by the time factor: the more time goes on, and some migrants are accepted (the good news are largely amplified by the effect of collective emotions), the more migrants consider staying at all costs, in the hope to be among the lucky ones.

To encourage more migrants to return home, Germany’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), launched in 2017 www.returningfromgermany.de, “a new online portal providing information for those interested in voluntarily returning to their home country, especially offering an insight into important factors such as medical provisions and the current labour market in the relevant home country, detailing financial schemes offered to people of a particular nationality while in Germany as well as reintegration programs available in their homeland.”[9]

The German government created several programmes to motivate migrants to return. The REAG/GARP-Programme (Reintegration and Emigration Programme for Asylum-Seekers in Germany / Government Assisted Repatriation Programme) covers travel cost, and offers travel assistance for migrants who lack the means to return voluntarily, among the asylum seekers, persons with a negative asylum decision, persons with a residence permit (e.g. recognised refugees), victims of forced prostitution or human trafficking.[10]

The programme StarthilfePlus provides financial start-up assistance for the migrants of specific nationalities, those from Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Gambia, Ghana, Iraq, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Egypt, Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Benin, Burkina Faso, China, Democratic Republic Congo, Ivory Coast, Georgia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, India, Cameron, Kenya, Lebanon, Mali, Morocco, Mongolia, Niger, Palestinian territories, Russian Federation, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam.[11] The StarthilfePlus has four stages:

Stage 1: You receive 1,200 EUR if you apply for an assisted voluntary return before the asylum procedure is completed. Stage 2: You receive 800 EUR if your asylum application has been rejected and you decide for a voluntary return within the period set for your departure. Stage S: You receive 800 EUR if you have a protection status according to German law and if you return to your country of origin with StarthilfePlus. Stage D – Only for people from Albania and Serbia (starting from 01.01.2018): If you have had a temporary permission to stay in Germany (“Langzeitduldung”) since two years or more and if you return to your country of origin with StarthilfePlus, you receive a one-time financial support of 500 EUR, as well as the following reintegration assistance in kind, based on your needs: Housing-related costs up to 2,000 EUR for families and up to 1,000 EUR for single persons; Medical costs up to 3,000 EUR for families and up to 1,500 EUR for single persons.[12]

2. Maximising the gain of return migration

Any measure has its effective side, but could be, as well, an opportunity for more abuse. It is true that some would use the money to spend their holidays in the country before attempting to come back, but such procedure should be accompanied by a dissuasive element, by for example, issuing punitive measures (repayment, prison etc.) which in any case, could be costly, and would discourage any second migration plan. This means of course overburdening the judiciary system, already saturated. In terms of risks, once the effect of the mass hysteria weakens, a considerable number of migrants make an unfavourable pain-and-gain calculus which could probably push more people to consider other solutions than migration: risking so much, in terms of money and safety, to live in camps (subject of violent attacks), then being offered a small amount of money with no better options offered, leads to conclude that the gain does not justify the pain. The key-factor of the success of such measure is the timing of the offer, while the migrant still does not have other options. Matthieu Delpierre and Bertrand Verheyden showed that “migrants make remittance and saving decisions at an early stage of migration, when their long-term economic performance in the host country is still uncertain. Over time, information about professional prospects is acquired, and conditionally on past decisions, migrants adjust their return plans”.[13]

Such measure has a dismantle effect on the hysteria of mass migration: the moment money is offered, the migrant is brought back to the bitter reality, and no longer considers the trip worth it, and his or her country of origin appears liveable. A certain amount of money could also appear a better option compared to an interminable administrative procedure, the handling of the individual in question.

Our conversations with several returned migrants show that currently a returned migrant typically develops a cynical and harsh perception of Europe, spreading it among his family members, close relatives, friends and acquaintances. It also introduces in the narrative about migration hurdles of the procedure, the camp, the restrictions and so on, which cool down the hysteria and raise uncertainty in would-be migrants. In a social environment that does not read or critically approach experiences of migration, usually building its plans on appearances (ex. photos of car and glittering cities), return migrations could instil counter-narratives about migration, bringing to minds that the expected gain is not worth the pain.

What is lacking both in the French and German return strategies, in spite of having good potential, is the cooperation with the sending countries. The latter are not involved enough in the return programmes. The sending countries ought to create departments of re-integration of migrants (within ministries of foreign, social and interior affairs), to assure the follow-up of the procedure, and the reinsertion of the migrants. Second, the sum of money offered could be meaningful in a country like Egypt, but almost insignificant in Turkey. It is therefore required that the funding of the start-up should be adjusted to the value of money in a specific country and according to the professional sector of the migrant.

Additionally, there seems to be little awareness of the importance of the family in return projects,[14] all the more that family reunification in the 1970s has put an end to the return plans of the first generation of guest workers to Europe. A study of Turkish migrants living in the United States concluded that in many cases, migrants’ return wishes pertain to family concerns, and particularly related to the ageing parents they have left behind in Turkey and to their children born in the US.[15] The suspension of reunification procedures in Germany in 2017 prevented bringing first-class relatives and relatives to 150,000 Syrians, 112,000 Iraqis and 26,000 Afghans.[16]

Migration itself being a family project, as family funds the trip, or puts its hopes in the migration project, it is expected that family members would join the migrant once the latter establishes the conditions of such move. The role of family in Africa and West Asia, extends beyond the role family plays in European societies; family being the strongest tie, the economic provider and the central pivot of identity, whereby any individual is but a mechanism within the big family, it is ordinary that once the migrant succeeds, and migration is seen as a social promotion, he or she would extend the success to the family members, or to at least pay back family in some way or another (for example through marriage).

As such, there can be a chance to convince migrants to return in so far as they did not initiate a process of family reunification or in case legislation makes it almost impossible for a migrant to bet on family reunification. In case of an easy procedure or if a migrant had enough time to initiate the procedure, there is little chance the migrant would return. Logically, the more complicated the procedure of asylum itself is or whatever status the receiving state wishes to provide to the migrant, the less attractive it would appear and for the migrant who provides for a family, return would be more of a gain. Considering the benefits the migrant could draw from its status as married with children, it seems more of a gain than a pain to stay, if the procedure is likely to succeed. People with families constitute a no-return point for the host country: they might well stay and never return.

A recent research by T. Kuhlenkasper and M. F. Steinhardt on return migration in Germany, published in December 2017 states that “a strong influence of family characteristics on return migration and that individuals incorporate the migration costs of family members into their individual migration decisions… having children is associated with a lower likelihood of outmigration among immigrants. Parents with children in kindergarten or school are likely to face high migration costs when moving to a foreign country. The negative relationship between outmigration and having children is particularly pronounced for Turkish immigrants”[17].

Usually, return is perceived as a failure in the sending societies, lived with guilt and shame[18], not only in that a migrant becomes again a burden to his family, a setback after all, but also in loosing the investment the family made in the trip, facing probably debts, and social inferiority, and more generally, pushing the migrant to become an undervalued social agent. Social cultures in sending countries from Africa and Asia, perceive returning migrants as social predators or hunters who brought nothing from Europe, which fuel the mass psychology of migration. For years, this could be a social stigma if the migrant does not receive support. It is, however, observed that the returnees who quickly reintegrate in their societies through work are valorised, even if the general economic situation of the country is not particularly thriving.[19] Valorisation of return is primarily the responsibility of source countries, but could be emphasized and assisted by host countries. A combined approach of a positive re-integration by the homeland and social programs (co-designed by host and source countries) could promote return as a new start. In the long run, institutional reforms especially social and economic reforms can further reinforce migrants’ aspirations to return.[20]

3. Limitations of return migration

One source of weakness in the return migration strategy is that it is an expensive strategy, and in spite of all efforts, can only achieve some results, namely engineering a counter-action and prevention of mass migration. Although return migration could be dissuasive to many migrants, who, more prudent would choose to invest in their social assets rather than embarking on the journey of migration, it is still a fact that most people would not return. In Western Europe, return strategy seems to be a ventilating solution, the function of which is to avoid saturation and social clash and fracture.

If decision-makers expect return migration to be a decisive solution to migration, then, it might be said, without hesitation, that return migration cannot work. In social engineering, nothing is decisive, in the sense that a solution can eradicate a problem, and only a concurrent set of strategies can reach the best possible results, in a given context, and only diminishing the number of migrants who stay in, to the limit possible. Moreover, experience shows that collaboration with southern countries to re-integrate returnees is another weakness in this strategy, and should be known that sending countries benefit from migration (exporting demographic surplus, social trouble, political contestation, income and economic stimulus from remittances etc.). Probably, and in a global manner, structures of collaboration are useful in that they allow more potential of pressure on these countries, while they could serve, hopefully, for mediation in case of mass return migration.

A key policy priority should therefore be to plan for rejecting mass migration at the outset. Any strategy of moving migrants once they enter can only achieve partial success. Migrants and NGOs build their plans on the saying that “once in, you are in”, and in most cases, this is factual, with all known social disastrous consequences of letting mass migration in. So the only solution, and the only optimal scenario, is that you do not allow the problem to happen, in the first place, by stopping mass migration to get in; it is also the less expensive and the most effective strategy.

Conclusion

There is a general consensus that addressing mass migration can only be effective if dealt with at its roots. Considering the factor of hysteria in mass migration, one suggested strategic solution integrates tools of mass disenchantment through organised return migration and procedures, to instil the reality that “there is no paradise”. Reversing migration, in its turn, could only be effective, partially and in the Western European context, if conducted at three levels: smart return programs in the host countries which take into account the pivotal factors of return, including family, combined with functional re-integration programs in the sending countries, and an accompanying social valorisation of returnees, in order to avoid re-migration, and dissuade other candidates. All things considered, these levels do not seem to coalesce in the foreseen time, and the only recommended strategy would be to reject mass migration in the first place.

[1] Key Migration Terms

https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms (last accessed 07 January 2018)

[2] European Commission – Speech, Jean-Claude Junker’s State of the Union Address 2017, Brussels, 13 September 2017

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-17-3165_en.htm (last accessed 07 January 2018)

[3] Bruxelles veut accélérer le retour de 1,5 million de migrants illégaux

http://www.lemonde.fr/europe/article/2017/09/27/bruxelles-veut-accelerer-le-retour-de-1-5-million-de-migrants-illegaux_5192251_3214.html#cKHCRDxT5L5miEhQ.99 (last accessed 07 January 2018)

[4] Migrants : la France propose 2 500 euros pour rentrer au pays

http://www.lemonde.fr/immigration-et-diversite/article/2016/11/24/migrants-2-500-euros-pour-rentrer-au-pays_5037518_1654200.html#BIwRFtw5igdAVpdS.99 (last accessed 07 January 2018)

[5] Migrants : la France propose 2 500 euros pour rentrer au pays

http://www.lemonde.fr/immigration-et-diversite/article/2016/11/24/migrants-2-500-euros-pour-rentrer-au-pays_5037518_1654200.html#BIwRFtw5igdAVpdS.99 (last accessed 07 January 2018)

[6] ‘Returning from Germany’ online portal to boost number refugees leaving voluntarily

http://www.dw.com/en/returning-from-germany-online-portal-to-boost-number-refugees-leaving-voluntarily/a-38797249(last accessed 07 January 2018)

[7] Idem.

[8] Idem.

In the year 2017, rejection of asylum applications in Germany reached 38.5% compared to 25% in 2016, and this refusal led to the number of candidates for return from Germany to more than 230000 people.

Lajiʼu Almania 2017: Tarajuʻ bi-l-aʻdad wa-muhaffizat li-l-rahil

http://www.aljazeera.net/news/reportsandinterviews/2017/12/28/لاجئو-ألمانيا-2017-تراجع-بالأعداد-ومحفزات-للرحيل

[9] ‘Returning from Germany’ online portal to boost number refugees leaving voluntarily

http://www.dw.com/en/returning-from-germany-online-portal-to-boost-number-refugees-leaving-voluntarily/a-38797249 (last accessed 07 January 2018).

[10] REAG/GARP

https://www.returningfromgermany.de/en/programmes/reag-garp (last accessed 07 January 2018).

[11] StarthilfePlus

https://www.returningfromgermany.de/en/programmes/starthilfe-plus (last accessed 07 January 2018).

[12] Idem.

[13] Matthieu Delpierre, Bertrand Verheyden, ” Remittances, Savings and Return Migration under Uncertainty “, IZA Journal of Migration 3, No. 1 (2014): 1-43.

[14] See

Stefanie Konzett-Smoliner, “Return Migration as a ‘Family Project’: Exploring the Relationship between Family Life and the Readjustment Experiences of Highly Skilled Austrians “, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42, No. 7 (2016): 1094-1114.

[15] Aysem R Şenyürekli; Cecilia Menjívar, “Turkish Immigrants’ Hopes and Fears around Return Migration”, International Migration 50, No.1 (2012): 3-19.

[16] Lajiʼu Almania 2017: Tarajuʻ bi-al-aʻdad wa-muhaffizat li-rahil

http://www.aljazeera.net/news/reportsandinterviews/2017/12/28/لاجئو-ألمانيا-2017-تراجع-بالأعداد-ومحفزات-للرحيل

[17] Torben Kuhlenkasper, Max Friedrich Steinhardt, “Who Leaves and When? Selective Outmigration of Immigrants from Germany”, Economic Systems 41, No 4 (2017): 618.

[18] Nauja Kleist ” Disrupted Migration Projects: The Moral Economy of Involuntary Return to Ghana from Libya”, Africa : Journal of the International African Institute 87, No. 2 (2017): 322.

[19] Etleva Germenji, Lindita Milo, ” Return and Labour Status at Home: Evidence from Returnees in Albania”, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 9, No. 4 (2009): 497-517.

[20] Angela Paparusso, Elena Ambrosetti, ” To Stay or to Return? Return Migration Intentions of Moroccans in Italy “, International Migration 55, No. 6 (2017): 149.

Photo: geo.tv