The Australian Model

or the island country’s answer to asylum and migration challenges of the past decades

Australia’s history of the past century, and the migration crises of the last two decades have led to both firm and less marked, but successful policy responses, which the European Union still lacks, although its interests would call for such. Is the Australian model of handling the refugee situation unique to its geopolitical characteristics, or could its components be adapted to other parts of the world?

Australia is a multicultural country, which has developed as an immigration society since its foundation in 1782, and it is a young one among its kind. Migration to this island country is still massive, culturally diverse, and multidirectional. But intense immigration meets with a level of awareness and control far exceeding that in Europe.[1]

Although settlers of the continent-wide country numbered only around 3.8 million at the end of the last century, the country already had appropriate structures to become a familiar and attractive destination of spontaneous migration, apart from the organized colonization conducted by the British Empire. Since India, China and Indonesia (called the Dutch East Indies at the time) were closer and far more populated than Europe, and as a protection of the gold mines located in Southeast-Australia, which the Chinese had a peak interest in, new methods were sought. The White Australia policy was instituted, which required certain familiarity with the English language (Immigration Restriction Act, 1901), and Australia could restrict immigration to people from Anglo-Saxon and (other) European countries (Miller, 1999:192). However, restrictions of the White Australia policy were gradually abolished between 1966 and 1973 (non-discriminatory policy), and although social empathy was at the same time gradually replaced with a fear of an economic setback (McKenzie – Hasmath, 2013:418), a multicultural immigration policy has been in place since then, with political manoeuvring set forth in detail below (National Museum of Australia, 2015). Per 2014 data, 28.1 percent of the 23.5 million Australian population (about 6.6. million people) were born abroad (OECD, 2016: 242), which is not high in world-comparison, but exceptional compared to the member states of the European Union.

The Australian governments of the 1980’s and the following decades were clear and definite on fashioning their immigration policy after the pressure of public opinion. This process is best described as the Liberal Paradox, „the trend amongst contemporary states towards greater transnational openness in the economic arena alongside growing pressure for domestic political closure” (McNevin, 2007:612). This period was not only marked with neoliberal economic reforms paving the way of privatization, a 15-year span of constant economic growth, and the highest employment rate of the last 30 years, but also with growing inequalities in society, caused by industry reforms, technology changes, and new workforce structures. Full-time employment declined in low skill jobs. This resulted in job insecurity and concerns for the future in a large section of society, which changed the foundation of asylum policy for the next period (McNevin, 2007:613-615).

In 1982, the Fraser government instituted the practice of individual asylum investigations for the first time in Australia’s history. The measure aimed to single out those arriving from the Indochinese area, who were not entitled to refugee status, as set out in the Geneva Convention of 1951 relating to the status of refugees. In 1983, the Hawke government endorsed the durable solutions proposed by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR), as an alternative to the „Indochinese refugee problem”. This proposed voluntary repatriation, or – in case it was not possible – protection in the country of first asylum. In case neither were feasible, the last resort was resettlement in a third country, such as Australia. Australia, along with 77 other countries, endorsed this action plan (Comprehensive Plan of Action for Indochinese Refugees) in 1989 (Phillips – Spinks, 2013:9-10). The definite purpose of this measure was to discourage refugees from the Indochinese area to head towards Australia, and to assist their settlement in the first country of no imminent danger.

However, the refugee problem became large scale only after 1998, and led to the development of a moral panic against illegal migration, as officially admitted. In the 1990’s, the Labour Party introduced the practice of mandatory detention, which made the country’s immigration policy even more strict. The most controversial form of detention was promoted by the Howard government: boat arrivals, attempting illegal entry to Australia were deported to offshore camps. This measure was introduced in response to the events of August 2001, when the Norwegian MV Tampa freighter rescued about 400, mostly Afghan refugees from the Indonesian Palapa boat in international waters, near Christmas Island in Australian territory. John Howard, the Australian Prime Minister denied the freighter access to Australian waters, and wanted to turn it back to Indonesia. Howard warned the captain that entering Australian waters would be a crime of smuggling in the 1958Migration Act, with the possible penalty of imprisonment and a fine of 110 thousand Australian dollars (Marr – Wilkinson, 2004:31). The diplomatic impasse was resolved by the so-called Pacific Solution, a measure still in place today. In accordance to this measure, Nauru and – making this case an exception – New Zealand accommodated the asylum seekers, while the Australian authorities processed their asylum applications. In this case, asylum seekers transported to New Zealand first received an asylum, and then citizenship (Frame, 2004:292).

In September of 2001, Howard referred to the acts of terrorism in the United States, and to the Tampa incident during his election campaign, and said the following, the rhetorical elements of which we can now observe in the European political arena: „military response and wise diplomacy and a steady hand on the helm are needed to guide Australia through those very difficult circumstances. National security is therefore about a proper response to terrorism. It’s also about having a far sighted strong well thought out defence policy. It is also about having an uncompromising view about the fundamental right of this country to protect its borders, it’s about this nation saying to the world we are a generous open hearted people taking more refugees on a per capita basis than any nation except Canada, we have a proud record of welcoming people from 140 different nations. But we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come” (Howard, 2001).

The Liberal-National coalition led by Howard adapted changes to legislation, which – in connection with the Pacific Solution principle – were the hallmarks of Australian border protection policy for the years to come (2001-2007), and still serve as the cornerstones of national immigration policy. The two amendments stripped the refugees arriving on sea from their right to make an asylum claim (lack of access to the procedure) by excluding the territory of the Christmas Island, the Ashmore and Cartier Islands, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands from the Australian migration zone. Thus, refugees arriving to any of these areas were not entitled to seek international protection from the Australian authorities. The country sought to bring the migration flow under regulation by a unilateral act, that of disannexing some of its own national territory. The amendments allowed for only one exception from the treatment outlined above: if and in so far as the respective Minister for Immigration determined that it was public interest to settle an asylum seeker arriving to an excised area in Australia, the way to initiate an asylum application was opened to that individual (Phillips – Spinks, 2013:16). The same Pacific Solution authorized the Australian Navy to intercept asylum seekers arriving by boat, and displace them interminably to a detention camp outside its territory, while the authorities decide on admittance (Fox, 2010:357). Note that the UNHCR was initially in support of deporting the refugees to Nauru, but only for security screening. When the international organization became aware of the true intent of the Australian government, it denied cooperation with the country’s leadership (Magner, 2004: 56).

Australia – to ease international pressure due to its asylum policy – introduced a so-called temporary protection visa in 1999. It can be issued to refugees who arrive irregularly, but reach the shores of Australia (’onshore application’), and are entitled to asylum status as set out in the Geneva Convention of 1951. The asylum applications are processed individually by the Australian authorities, and the country of origin remains monitored for its public security situation even if protection is granted, so that the person in protection can be sent home once conditions allow. Individuals not eligible for protection are sent back to their country of origin as soon as possible.[2] Those with temporary protection visas have limited possibilities to start with: the visa is valid for three years only, it does not give right to family reunification, and it allows the leave of the country only in particular circumstances (and – in accordance with the rules of the Geneva Agreement – never to the country of origin). It does not provide access to other types of visa or Australian citizenship, but the visa holder is entitled to employment, and use the Australian social and healthcare services.[3]

The Howard immigration policy was highly successful from its start to the change of government in 2007. The three major measures of the Pacific Solution[4] highly reduced the number of irregular immigrants arriving by sea in the decades to come: In 2001, 43 ships and 5516 people arrived, while in between 2002 and 2007, only 18 ships and 288 people arrived to Australia by sea (Parliament of Australia, 2016).

However, the Labour Party coming to power in 2007 set down a whole different direction in foreign policy, especially with regards to refugees. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd pledged cooperation to UNHCR, and wanted to keep Australia’s middle power status (Rudd, 2008). Rudd started with a harsh declaration against the Pacific Solution, and criticized Howard for diminishing Australia’s international reputation by the inhuman treatment of refugees. To break away from the Pacific Solution, Rudd closed the refugee camps in Nauru and Papua New Guinea, revoked the temporary protection visa, and – although with limits – provided legal representation for asylum seekers with denied applications. Still, Rudd did not break away completely from the former immigration policy, since the islands „excised” from Australia’s migration zone were not taken back, and refugees arriving there were still considered irregular migrants.

At the end of the Rudd government’s mandate, in the 2010 campaign period, the two most popular parties, the Liberal Party of Australia and the Australian Labour Party referred to citizens of third countries with irregular arrival methods as threats to Australia’s sovereignty, national values and territorial integrity. The change in the Labour Party’s immigration policy was most likely induced by a new leader of the opposition, Tony Abbott, who proclaimed zero tolerance for refugees arriving by sea. He criticized the Labour Party repeatedly during the campaign period for adopting an overly permissive policy, relaxing the Pacific Solution practice, and amounted to the loss of efficiency in border control (McDonald, 2011:281-286).

A prime initiative planned by Abbott was the stop the boats policy, a key component of the four cornerstones used in the campaign of the Liberal-National Coalition (McDonald, 2011:287). Abbott resonated with Howard’s campaign speech before the 2001 elections with this argument: „we (Australians) decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come” (Abbott, 2013). He also stressed that we live in a world, where crime and terrorism know no limits, and pose a new challenge to the border control system of developed countries. A naive and soft immigration policy defies common sense. The most important duty of governments should be to care for their own citizens in the first place. In extending this care to citizens of other nations, one should consider the effects this would have on the well-being of local citizens. (Abbott, 2010).

Although the Liberal-National Coalition did not make it to government in 2010, the appearance of Tony Abbott posed a real challenge to the Labour Party, which in turn replaced Kevin Rudd (Pannett, Rachel 2010). His successor, Julia Gillard was hesitant to take a firm stand on immigration policy at first, but then committed to strict measures as a Prime Minister, as opposed to Rudd,Gillard, called for a fight not against the refugees, but against the smugglers who take them through international waters, and intended to stop the boats before departure, thus undermining the network of smugglers. The Prime Minister referred to irregular migration as a global challenge, and considered it as a problem, which – by nature – could only be solved globally, with the cooperation of nations. She urged the formation of a regional cooperation in between the pacific countries and the UNHCR, which could effectively single out irregular migrants by through inspections. This would be a huge setback for the human smuggling business, since less people would risk the expensive and dangerous trip, knowing that they’d most likely not get through the Australian border (Gillard, 2010). In the spirit of this policy, she conferred with East Timor and New Zealand about erecting regional reception centres there, but her initiative failed (Westmore, 2010). At the same time, Gillard started negotiations with UNHCR, assuring the organization that Australia did not intend to go back to the Pacific Solution. Rather, it was interested in achieving a regional cooperation, effective on the long run. With this policy, the Labour Party wanted to let asylum seekers know that travel by sea was still not advisable, as a positive response to their application could not be guaranteed (Gillard, 2010).

When East Timor fell through, Gillard entered a bilateral agreement with Malaysia (People Swap), which stated that Australia would take 4000 refugees located in Malaysia, for Malaysia to settle 800 refugees en route on boat to Australia. The concept was crashed by the resistance of the High Court of Australia, which considered the agreement unlawful, saying that Malaysia did not have legal commitments to provide refugee protection according to Australian laws, since Malaysia did not ratify the Geneva Convention of 1951, or the 1967 Protocol amending it, so asylum seekers arriving in Malaysian territory could be sent to prison or expelled any time. Although the Gillard government – despite of the above-mentioned ruling – tried to pass a law amendment proposal in September 2011 and in June 2012, the notion could not succeed without support from the coalition of opposition parties and The Australian Greens (McKenzie, Hasmath, 2013:417).

Gillard’s immigration policy concerned not only the asylum seekers, but those citizens of third countries who were in Australian territory without meeting the requirements of lawful residence. The first major accomplishment was a triparty declaration with the Afghan government and the regional representative of UNHCR, which made it possible to repatriate Afghan citizens with asylum applications denied by Australia. With this declaration, the government sent a message to illegal migrants as well. As Chris Bowen, the Immigration Minister of the time said: „to dissuade people from risking their lives by joining people smuggling ventures, it is important that Afghans found not to be owed protection by Australia are returned to (their country of origin)” (quoted by Phillips – Spinks, 2013: 11).

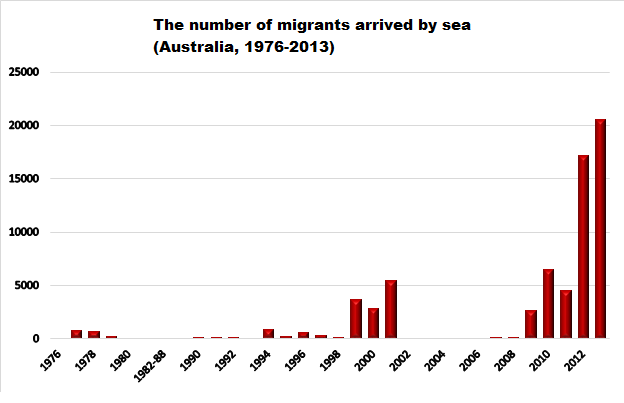

Nevertheless, the immigration facilitation measures of Rudd and Gillard brought a significant growth of numbers with regards to migrants arriving by boat –primarily due to firmness of action on part of the target group, and suitable communication on part of the human smugglers – during the government period of the Labour Party. The smugglers enticed people with false promises, and they boarded with trust in the inclusion policy of the Labour Party. The following numbers illustrate the process: in 2008, only 7 ships arrived at the Australian shores, with 161 migrants, while in 2010, there were 134 ships and 6555 people, and in 2013, there were 300 ships and 20 587 illegal migrants (Parliament of Australia, 2016).

Since more and more people undertook this dangerous and irregular way of entry, supporting the smugglers, this process also brought a raise in numbers of people lost at sea. According to the data base of Monash University, almost 1200 individuals died in open waters during the government period of the Labour Party (Australian Border Death Database).[5]

Due to the measures taken by Tony Abbott, who was elected the Head of Government in the meantime, the number of migrants arriving illegally by sea went down to 160 people and only one boat by 2014 (Phillips, 2015). Following Abbott’s election victory in 2013, Australian immigration policy – with minor changes – returned to the Howard-practice. In 2014, Abbott reinstalled the temporary protection visa cancelled by Rudd, which imposed strict constraints on the possibilities and rights of migrants arriving illegally. Another important change was brought by the Operation Sovereign Borders, in which the government authorised the military to deal with asylum seekers arriving by boat. According to this provision, military boats continue to patrol the Australian shores. They are to intercept, turn back, or when justified, tow back ships with asylum seekers to Indonesia. If and in so far as they reach Australian territory, then, in the former practice, the substantive examination of escape reasons will take place on Christmas Island. From here, they are taken to reception centres in Nauru or in Papua New Guinea. This practice strains Indonesian-Australian relationships, as – according to Indonesia’s official positon – Australia violates international law with this procedure in connection with the above-mentioned ships. From a legal point of view, this depends on the exact place of ship interception. Australia and Indonesia have both signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS – the Law of the Sea treaty, which sections international waters into zones. According to this treaty, Australia’s safety interests are protected by territorial waters out to 12 nautical waters from the baseline of the continent and its territories (including Christmas Island, along with the Ashmore and Cartier Islands, all of which are excised from Australia’s migration zone), and the country’s sovereignty is inviolable within that zone (Kovács, 2006:577).

Abbott’s stop the boat policy – like several of his predecessors – sent a message to refugees to not even try to approach the shores of Australia, since they would be turned back anyway, or at least deported to Nauru, or the Manus Island of Papua New Guinea.

Abbott holds that Europe should follow the Australian example in its immigration policy. He put it this way on September 18th, 2016, in Prague: Effective border control is not for the overly sensitive minds, but it is essential to save lives and protect the nations. The only viable option is to stop the boats, and thus, stop the open water casualties – (no wonder that) there has been no ships arriving illegally to Australia, and no one drowned in the sea along the way. By stopping the boats, we can take more real refugees needing protection, since the fate of applicants is decided by Australia, and not by the people smugglers. (see Abbott, 2016)

Malcolm Turnbull, Abbott’s successor, president of the current Liberal-National Coalition, continues Australia’s stop the boats policy. This policy’s efficiency is shown by the fact that under Turnbull’s government, Australia could raise the number of refugees admitted through the Humanitarian Program. As Turnbull put it at the September 19th, 2016 UN Refugee Summit: by stopping the boats, we can provide real help for the refugees. Without this certainty (that we can successfully stop the sea arrivals), we could not have raised the refugee quota, and extend one of the world’s largest permanent resettlement program by 35 percent. We could not have afforded to take an additional 12 thousand refugees from Syria and Iraq. (see March, Anderson 2016)

In closing, it is worth to note that Australia – under severe pressure from the international community for its unprecedentedly strict asylum policy – recently allowed for extraordinary migration-control solutions, when it tried draw an agreement with the Philippines, Canada and Malaysia, and – upon failure – signed one (Memorandum of Understanding) with Cambodia in September 1914. This agreement is unique in a sense that a traditional relocation country (receiving refugees) agreed with a developing (traditionally not receiving refugees) country about refugee reception. This is another way for Australia to find a solution to the situation of about two thousand people in Nauru and the Manus Island of Papua New Guinea, who meet certain preconditions. The memorandum of understanding provides framework for a program with a 55 million Australian dollar aggregated budget, and it is about citizens of third countries, originally applying for asylum in Australia, and placed in Nauru Island to wait out the procedure. Upon receiving asylum, they could be voluntarily settled in Cambodia, financed in its entirety by the Australian government. The fact that only about 10 people participated in this program since it was launched, and most of these are no longer in Cambodia, invokes recent European experiences. Some have returned to their country of origin, even though they might have left it to protect their lives. True, the great measure of secrecy around the agreement, the lack of available information about several important factors (for example, the agreement’s time frame; the participants’ rights and the services) and the opposing statements go against effective execution. Knowing the antecedents, it is understandable that the Australian government resorts to such extraordinary constructions to handle the stress of migration in that corner of the world. Nevertheless, people deterred in these islands can seek to succeed only within the framework of the above mentioned special visa types and – now somewhat relaxed – residence conditions[6]. Relocation into Australia or into another country is practically hopeless, at least according to the official statements (Gleeson, 2016).

Abbott, Tony (2016): „Tony Abbott lets fly at Russia and EU’s lax border control in Prague”– The Australian – Access: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/tony-abbott-lets-fly-at-russia-and-eus-lax-border-control-in-prague/news-story/b184ffd903508b62c99982bff115a3da (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Abbott, Tony (2013): „Tony Abbott evokes John Howard in slamming doors on asylum seekers – The Sydney Morning Herald” Access: http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2013/tony-abbott-evokes-john-howard-in-slamming-doors-on-asylum-seekers-20130815-2rzzy.html (Downloaded: September 22, 2016.)

Abbott, Tony (2010): „Address to the Australia Day Council. Australia Day Dinner, Melbourne”Access: http://australianconservative.com/2010/01/tony-abbottaustralia-day-has-many-meanings/ (Downloaded: May 14, 2015.)

Australian Border Deaths Database: Access: http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/thebordercrossingobservatory/publications/australian-border-deaths-database/ (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Parliament of Australia (2016): The official website of the Parliament of Australia: www.aph.gov.au (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Fact sheet – Australia’s Refugee and Humanitarian programme Access: https://www.border.gov.au/about/corporate/information/fact-sheets/60refugee#d (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Fox, Peter D. (2010): „International Asylum and Boat People: The Tampa Affair and Australia’s Pacific Solution.” Md. J. Int’l L. 25: 356-373. Access: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1529&context=mjil (Downloaded: September 20, 2016.)

Frame, Thomas R. (2004): „No Pleasure Cruise: The Story of the Royal Australian Navy.”Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. 1-352.

Gillard, Julia (2010): „Moving Australia Forward”Speech to the Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney, 6 July. Access: http://www.lowyinstitute.org/files/pubfiles/Moving-Australia-forward_JuliaGillard-PM.pdf (Downloaded: April 14, 2015.)

Gleeson, Madeline (2016): The Australia-Cambodia Refugee Relocation Agreement Is Unique, But Does Little To Improve Protection.Migration Policy Institute. September 21, 2016. Access: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/australia-cambodia-refugee-relocation-agreement-unique-does-little-improve-protection (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Howard, John (2001): John Howard’s policy speech.Australian Politics 28 October. Access: http://www.australianpolitics.com/news/2001/01-10-28.shtml (Downloaded: September 22, 2016.)

Illegal Maritime Arrivals (2016): Applying for a protection visa. Access: http://www.ima.border.gov.au/en/Applying-for-a-protection-visa/Temporary-Protection-visas (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

IOM (2016): Migration Flows – Europe. Access: http://migration.iom.int/europe/ (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Kovács, Péter (2006): International public law.Osiris Kiadó. 1-674. ISBN 9789632762104

National Museum of Australia, 2015: 1966: Holt government effectively dismantles White Australia policy Access: http://www.nma.gov.au/online_features/defining_moments/featured/end_of_the_white_australia_policy (Downloaded: December 4, 2015.)

Magner, Tara (2004): „A less than ‘Pacific’ solution for asylum seekers in Australia”International Journal of Refugee Law 16.1: 53-9.

March, Stephanie, Anderson, Stephanie (2016): „UN refugee summit: Malcolm Turnbull and Peter Dutton tout Australia’s immigration policy”– ABC.net.au – Access: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-20/australia-urges-un-nations-to-adopt-its-border-control-policy/7860160 (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Marr, David and Wilkinson, Marian (2004): Dark Victory – Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, Australia, ISBN: 1 74114 447 7, 1-480.

McDonald, Matt (2011): „Deliberation and resecuritization: Australia, asylum seekers and the normative limits of the Copenhagen School.”Australian Journal of Political Science 46.2: 281-295.

McKenzie, Jaffa and Hasmath, Reza (2013): „Deterring the ‘boat people’:

Explaining the Australian government’s People Swap response to asylum seekers.” Australian Journal of Political Science, 4: 417-430

McNavin, Anne (2007): The Liberal Paradox and the Politics of Asylum in Australia. Australian Journal of Political Science, 42:4, 611-630.

Miller, Paul W. (1999): Immigration Policy and Immigrant Quality: The Australian Points System. The American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 2. 192-197.

OECD (2016): International Migration Outlook 2016.Access: http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/social-issues-migration-health/international-migration-outlook-2016_migr_outlook-2016-en#.V-ZHrDUw7IU#page1 (Downloaded: September 25, 2016.)

Pannett, Rachel (2010):“Australia’s Rudd Calls Vote on Leadership”.The Wall Street Journal. Access: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704629804575324534190936548 (Downloaded: September 22, 2016.)

Phillips, Janet, and Spinks, Harriet (2013): „Boat arrivals in Australia”Access: http://sievx.com/articles/psdp/20130129BoatArrivals1976-2013.pdf (Downloaded: September 19, 2016.)

Phillips, Janet (2015): „Boat arrivals and boat ‘turnbacks’ in Australia since 1976: a quick guide to the statistics” Access: http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/BoatTurnbacks (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

Rudd, K. (2008): „Hard Heads, Soft Hearts: A Future Reform Agenda for the New Australian Government.” Speech at Progressive Governance Conference, London, 4 April 2008.

Westmore, Peter (2010): ’Why Gillard’s ‘East Timor solution’ cannot work’ News Weekly – Access: http://newsweekly.com.au/article.php?id=4369 (Downloaded: September 23, 2016.)

[1] Although this analysis does not investigate the question in detail, it is worthy of note that Australia has been operating several programs with various focuses and top limits to keep legal migration under control. Namely: The Migration Programme (with a separate programme for family members, and several subprograms for highly educated people), the Humanitarian Programme (for a yearly quota of 12-14 thousand people awaiting resettlement under international protection), and the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement (a separate programme established in 1973, regulating the stay of New Zealand citizens) (Miller, 1999:192).

[2] Note that similar constructions are available in other countries of the world and in several member states of the European Union – one example is the humanitarian visa.

[3] This visa type was later augmented with another visa type for employment or education (Safe Haven Enterprise Visa) for – and we’d like to emphasize this again – migrants who arrived illegally (Illegal Maritime Arrivals, 2016).

[4] 1. Exempting certain islands from the Australian migration zone. 2. Authorizing the Australian Defence Force to intercept boats that carry illegal migrants. 3. Deporting illegal migrants to Nauru and Papua New Guinea

[5] For the sake of comparison, note that over 3500 people lost their lives on the Mediterranean Sea in Europe during the first nine months of 2016 (IOM 2016).

[6] Detention status was lifted in October 2015 in Nauru, and in May 2016 in Manus Island, and these became open facilities. The new regulation provides free movement for facility residents within a limited territory, but it can be a source of conflict with the local residents.